The offshore business of Belcorp’s popular insurance policy

The beauty multinational Belcorp and the Swiss insurance company Paralife designed a complex legal scheme in Bermuda to bypass Peruvian laws and create a micro life insurance policy outside the control of the Superintendency of Banking, Insurance and AFP. Over the last six years, more than one hundred thousand cosmetic product vendors in Peru and four other countries in the region have purchased this policy, launched in 2011 as a service targeting women on the lowest incomes.

In September 2016 a group of 160 executives from Latin American corporations traveled to Bermuda to meet with experts from the insurance industry who were offering them the opportunity to be part of an emerging offshore business in the region. The product was a service designed especially for large companies so that they could control funds from the policies they issued and remain far from the reach of any supervisory body. While they enjoyed a sunset cruise on the Great Sound Bay, a number of the guests were presented with the proposal by an exclusive law firm offering to make their projects come to fruition in this 54-square-kilometer tax haven known as the world capital of risk. "We now have 200 Latin American companies who are investing in this insurance market and we continue adding more customers," said Eduardo Fox, Latin America manager for the Appleby law firm and one of the principal promoters of the event.

This Mexican economist was already a well-known figure amongst the business elite that uses the island’s discreet services: for 26 years he has been part of the famous law firm which boasts of belonging to the so-called Offshore Circle Magic, consisting of the world’s largest legal firms operating in tax havens. Fox is also Latin American affairs adviser to the Government of Bermuda, as well as a director of the Latin American Association of Risk and Insurance Managers, and is a guru for the so-called captive insurers—offshore companies formed to transfer and administer funds from the risk coverage of a parent company or one of its subsidiaries. Fox’s name appears 7492 times in the 6.8 million leaked Appleby documents to which Ojo-publico.com gained access as part of the global investigation known as the Paradise Papers, a project led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung.

RISK CAPITAL. Bermuda is the center of operations for the offshore insurance industry. / ICIJ

Dozens of emails, business records, bank requests, and other files reviewed by our team of reporters reveal how Eduardo Fox advised corporations in Peru, Colombia, Mexico, Argentina, and Chile on how to set up or lease offshore companies that would manage risks, save tax, and keep them beyond the reach of supervisory bodies. Among its clients, we identified the beauty products multinational Belcorp, which, together with the Swiss company Paralife, created a micro life and hospitalization insurance policy that circumvented the regulations of the Peruvian insurance system through a complex legal scheme designed in Bermuda.

An offshore company beyond the jurisdiction of Peru’s Superintendency of Banking, Insurance and AFPs (SBS) holds fifty percent of the liability for this policy, launched in 2011 by Belcorp as a corporate social responsibility project supporting sellers of beauty products. Yet in the last five years, this product has been acquired through the RIMAC and Protecta insurers by more than one hundred thousand Peruvian employees of the company that the magnate Eduardo Belmont controls in 16 countries in the region. Ojo-publico.com has verified that the policy has also been purchased by thousands of beauty consultants in Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, and Mexico using the same system: the subsidiary Paralife Re is the party ultimately liable for the micro-insurance despite the fact that it lies out of the reach of the local agencies that supervise the insurance industry in each country.

The insurance policy for beauty consultants

Estela Pérez is a Belcorp cosmetics salesperson who works at a hairdresser on Benavides Avenue in Miraflores and offers Esika and Cyzone beauty products. Three years ago, she learned about the micro-insurance policy known as Familia Protegida during a phone call from a company representative inviting her to join. The cosmetician decided this policy represented a good opportunity to obtain life and hospital expenses insurance her two children: the proposed payment was affordable and the only prerequisite was that her sales be regular. "They offered us basic insurance for 7.5 soles. It was a not-to-be missed opportunity and I accepted", she told Ojo-publico.com

CLIENTS. The Belcorp micro-insurance was designed for all the corporation’s beauty consultants in Latin America. / Belcorp

Whilst this young single mother is yet to call on the policy, she is aware it obliges Protecta to pay a fixed sum of some US$3,000 in event that she or one of her children die, and US$12 per day in the event of admission to a hospital or clinic because of an accident or illness. Perez is listed as a policy holder on a database we found among the leaked Appleby files. Like most of the other employees, she is unaware that the design of her policy resembles a Russian babushka doll and that the party ultimately liable is beyond the reach of Peruvian authorities.

Protecta is just the front company for an insurance policy in which the final link in the chain is an offshore company operating in the Bermudas: the subsidiary Paralife Re, of the Swiss corporation Paralife. It has solid links with Belcorp in the offshore insurance business given that Belcorp's financial strategy director sits on its board. Between 2011 and 2015 Pedro Malo occupied both positions. According to the ParaLife website, these are currently held by Gisele Remy.

THE TEAM. Eduardo Fox (left) and Timothy Faries manage Appleby’s services in the region. /OjoPublico

"We are the only corporation in the region that provides its consultants and members of their families with life insurance and hospitalization assistance created with the objective of providing them greater social security," said Jessica Herrera, Corporate Vice President of Belcorp, during a public presentation of the micro-insurance in Lima at the end of 2011. The same claim is often made by the transnational company’s spokespersons in Bolivia, Mexico, and Chile about a product aimed at the company's army of vendors, who every day labor like worker ants distributing all manner of beauty and personal care products. Thanks to their efforts, Belcorp achieves an average annual income of US$2 billion dollars.

The creation of the Familia Protegida (Protected Family) micro-insurance policy occured in the same year that Belcorp was included in the top 10 list of the best companies to work for in Peru.

This is how it worked

In March 2011, the Latin America manager for Appleby, Eduardo Fox, asked the officers of the law firm, Ken Goertzen and Jon Bardola, to take on a new business: Familia Protegida, the micro-insurance that Belcorp would offer to its Latin American salespersons as part of a generous display of corporate social responsibility. The request was recorded in an email that now appears in the Paradise Papers.

In creating the policy, the corporation, owned by the billionaire Eduardo Belmont, would operate with a strategic partner—the insurer Paralife. This company, owned by the Swiss national Rolf Hüppi, opened in 2006 to provide micro-insurance aimed at disabled people, low-income earners, or informal workers unable to access traditional insurers. At its inception, the veteran insurance tycoon’s concept was so innovative that Paralife captured the attention and support of the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the Andean Development Corporation, organizations that all became shareholders in 2007.

THE SCHEME. The law firm Appleby advised Paralife to design Belcorp's micro-insurance offshore business.

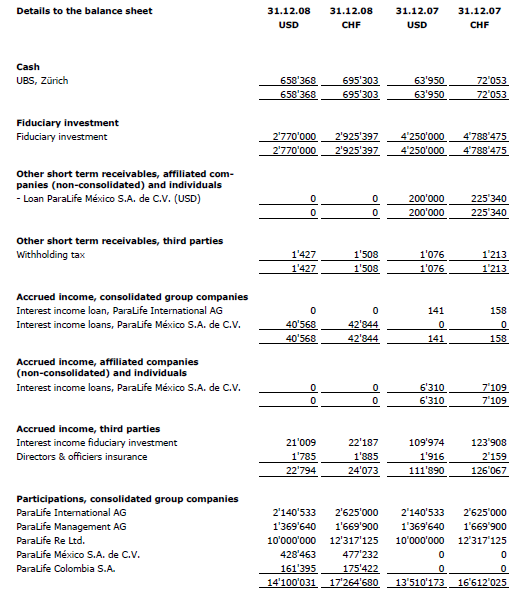

Paralife does not have the appearance of a profitable business. But it is. This corporation, based in Zurich, operates through a captive insurer registered in Bermuda: Paralife Re. It is Hüppi’s offshore company that assumes the risks of its clients, without itself being subject to supervision by the regulatory institutions of the countries where the policies are sold and their beneficiaries are located.

Corporations seeking a strategic partnership with Paralife must accept the Russian doll structure that this Swiss company utilizes. It normally includes an intermediary: Swiss Re, a reinsurance company with international credibility.

CONTRACT. This is one of the three documents that prove the participation of Belcorp, Paralife, Swiss Re and two insurance companies in Peru.

In the case of the Belcorp micro-insurance, the local front insurance companies were RIMAC and Protecta. And the reinsurer was Swiss Re. All this information about Familia Protegida is registered by the SBS. And with good reason. Peruvian regulations require that all foreign reinsurers signing a contract with a national insurer comply with at least one of a set of established criteria, including a vulnerability-free rating granted by one of the principal international risk ratings agencies: Moody's, Standard & Poor's, AM Best, or Fitch Ratings. Swiss Re held three of these four certifications. However, Belcorp’s micro-insurance was transferred to the offshore company Paralife Re, which fell outside the jurisdiction of the SBS.

Proof that this business model—implemented with the advice of Appleby—was in operation, is found in three contracts that confirm the participation by RIMAC, Swiss Re, and Paralife Re in Belcorp’s micro-insurance. According to documents reviewed for this report, Protecta also participated in a second phase, in which the sequence and scope of the operation were repeated.

LIMITED CONTROL. The Superintendency of Banking, Insurance and AFPs (SBS) lacks the authority and mechanisms to regulate captives. / Mayté Ciriaco.

The first contract was signed on 30 May 2011 between RIMAC, represented by its executives Rodrigo Gonzáles and Luis José Pardo, and the reinsurer Swiss Re, represented by Fredy Shopflin and Annemarie Loosli. According to the agreement discovered in the Paradise Papers, RIMAC transferred 50% of the micro-insurance risk from Belcorp to Swiss Re, so that when policyholders claimed on their policy, each company would meet half the costs.

The majority of the employees with micro-insurance have no idea that the design of their policy resembles a Russian babushka doll.

Six months later, in November 2011, Swiss Re and the offshore Paralife Re signed a second contract. This time, the Swiss reinsurer transferred to Paralife Re 100% of the risk entailed in Belcorp’s micro-insurance. In return, Swiss Re, transferred 50% of the monthly income from the premiums paid by its policy holders. In this way, the offshore company Paralife Re took final responsibility for the risks of its Peruvian members, but without any oversight by Peruvian authorities. Although Paralife group’s official website highlighted the services it provides in Peru, on the face of it, the company had no Peruvian clients.

Neither Paralife Renmor Swiss Re were ever mentioned to Belcorp’s insurance policy holders, who were shown only a Familia Protegida contract in which the liable parties were RIMAC (between 2011 and 2013) and Protecta (from 2013 onwards).

Belcorp’s partner

Several years before becoming a strategic partner of Belcorp in Peru, Paralife had started business in the region through subsidiaries in Mexico and Colombia. The Paradise Papers now reveal that, at least in the latter case, the start-up was far from regular. An email dated 17 February 2010 sent by Rulf Hüppi himself to Appleby employee Adrián Alhassan reveals the former’s interest in officially establishing Paralife’s Colombian headquarters. However, the company had been in operation since 2008: an audit conducted on 31 December of that year showed it to be already reporting earnings.

PARTERS. Belcorp and Paralife came together to create an offshore micro-insurance scheme in Bermuda.

Hüppi’s email conversations with Appleby advisors inquire about the need for ParaLife Holding AG, the group’s parent company, to open a subsidiary in Colombia to carry out its operations. The corporation normally arranged a loan from its parent company to the new subsidiary when seeking to expand. It had used this system to form Paralife Mexico. However, according to Húppie emails, this type of loan was restricted in Colombia unless the company providing the loan was subject to some form of regulation.

De: Ken Goertzen

Para: Brad Adderley

Asunto: ParaLife Re - Bermuda Anti Money Laundering legislation

For this reason, according to the Swiss magnate, Colombian authorities had suggested that his offshore company ParaLife Re could grant the loan for his new subsidiary, as this business was regulated by the Bermuda Monetary Authority (BMA). Hüppie sought to confirm that his offshore company had anti-money laundering certification in Bermuda. Appleby's lawyers replied it did not. They instead proposed another strategy: "If the request was sufficiently important, Appleby could get the BMA to grant the offshore company a good conduct report."

On February 22, five days after his first email, Hüppi replied that he would look for another way to establish his subsidiary in Colombia.

Unanswered questions from Belcorp

At the end of 2016 Belcorp’s micro-insurance sales area was still calling its beauty product sellers in Peru to convince them to purchase the policy. In a response to questions sent by Ojo-publico.com for this report, the corporation indicated that there are currently 22,000 policy holders in Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Bolivia, and Peru. This is four times less than the figure that appears in a database of Peruvian Familia Protegida affiliates found among documents attached to an email of January 2015 appearing in the Paradise Papers. Belcorp did not answer our follow-up question about the source of this discrepancy and whether it is due to mass abandonment by policyholders, or is simply an error in the response to the initial question.Another question left unanswered by the transnational was the implication of strategic partnership with Paralife mentioned in the communication of 25 October with Ojo-publico.com.

Paralife’s participation should have been included in the official documents for the Belcorp policy provided to the SBS in 2011. But we now know that it was not.

SBS replied by email on the activities of the Swiss Paralife and Belcorp as follows: "[This company] is subject to the rules issued by SBS for contracting reinsurance, provided that national insurance and national reinsurance companies participate". The answer makes clear that Paralife should have been included in the official documents for the Belcorp Familia Protegida policy reviewed by the auditing entity in 2011. But we now know that it was not.

AUDIT. This document shows that the Colombian subsidiary of Paralife has existed since 2008.

"We supervise the operations carried out by the insurance companies established in the country through the contracts, the quarterly information they report, and annual inspection visits to their premises," SBS indicated. However, its spokesmen did not specify if in this case it would take administrative action.

With regulatory authorities limited in their capacity to oversee the offshore insurance industry, the market continues to grow in leaps and bounds across the region. A report by the consultancy Marsh Captive Solutions reveals that Latin America has had the highest worldwide growth in the establishment of captive insurers: 11%. This is news that business operators in Bermuda toast with the island’s same emblematic Gosling rum they provide to guests on their cruises.

Cover photo: Mayté Ciriaco

#ParadisePapers

#ParadisePapers